Iliotibial Band Syndrome

Dr. Marc A. Bochner on

Dr. Marc A. Bochner on  Monday, April 12, 2004 at 07:50AM

Monday, April 12, 2004 at 07:50AM This month we are discussing the second most common knee injury in running, iliotibial band syndrome. ITBS shares some common causes with patellofemoral pain syndrome, and requires a similar approach to treatment. However, while the pain of PFPS can be sometimes be "run through" during treatment, doing so with ITBS will prolong treatment and recovery time. In fact, the severity of the pain will often prevent any running at all.

I have had this injury myself and have treated many bewildered runners who have been confused by this injury. To understand this injury, it is first necessary to know the anatomy and function of the iliotibial band. It does have a purpose besides causing agony and frustration in many runners. The band is actually a tract of ligament-like connective tissue. It runs from two muscles, the tensor fascia latae on the outer hip and gluteus maximus on the buttocks, along the outer thigh, and attaches at the outer patella and tibia at the knee. It lies between the hamstrings and quadriceps along this path, and allows all of these muscles to stabilize the outer hip and knee.

Distance running requires a great deal of force to be absorbed while moving forward from one leg to the other. Much of the stability required to do this comes from the outer hip, thigh, knee, and calf muscles. They work to control the standing thigh’s inward movement and to prevent the pelvis from dropping to the opposite, non weight-bearing side. Problems occur when any of those muscles, and the iliotibial band, becomes fatigued and tight. Once they do so, pain can occur in two ways. One is from the tightened band now not having enough length to allow proper knee flexion, leading to painful rubbing (friction) of the band at its insertion at the knee (and less commonly, at the hip). The other is from trigger points (knots) and adhesions forming in the muscles and band and referring pain to the outer knee and even the lower leg.

Unfortunately, the symptoms of tightness are often either not noticed or are ignored. In the typical scenario, pain will then develop along the outside of the knee, the outer hip and/or the thigh, during running. It may be a mild ache at first, but with further running and more tightening will be sharper and may force you to stop running. Often there is a specific time in your run where running is no longer possible- the knee feels as it is being squeezed in a vice, and must be kept straight to avoid the burning pain. At this point, many think they have a stress fracture or torn ligament/cartilage. But the strange thing about ITBS is that once you stop running, the pain often miraculously disappears within minutes, especially in early stages, and you can walk pain-free! That is why people often try to run again only to have the process repeat itself. With further progression, however, bending the knee will remain very painful for at least 24 hours after a run, and if you haven’t sought treatment yet, you now will.

Acute treatment depends on how far the injury has progressed. If you cannot bend the knee, stopping running and applying ice to the tendon by the knee is the first step. If there is significant swelling at the knee, office treatment with electrical stimulation and ultrasound may be necessary. At any stage, stretching of the outer hip and thigh must begin immediately, along with manual Active Release Technique of the tightened fibers and adhesisons. Patients often have significant relief of pain and increased range of motion with two to three of these specific soft-tissue treatments. Activities that usually can be tolerated include swimming and possibly light cycling, however cycling easy may still irritate. Sports that don’t require repetitive knee flexion and extension, such as tennis, may be tolerated before running can.

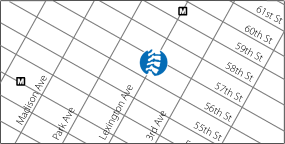

Full treatment involves addressing why the band, hip and thigh muscles lose their proper length- the causative factors. I often see patients who have had previous treatment without relief because only the knee was addressed. The entire lower extremity from the lower back to the foot must be checked. Training errors may include excessive downhill running, always running on a cambered road (outer leg) in the same direction (Central Park!), rapid increase in mileage or long run length, and racing too often. Mechanical faults may include tightness of the calf, hip flexor and hip adductor muscles, and weakness of the hip abductors. Other factors may include a wider than normal band, bow-legs, and underpronation or overpronation. All of these factors may make it more difficult for the band tissues to remain relaxed during the repetitive motion of running. Once the acute pain has subsided, continuing treatments include adding strengthening exercises(see below), continued stretching, further muscle treatments, spinal and hip adjustments for proper pelvic motion, orthotics if necessary, and correcting training errors. When the exercises can be performed pain-free resuming running can begin. Start with 100 yard strides at first, building to continuous running of 10 minutes and then adding time in 5 minute increments. Once you can run 45 minutes pain-free, regular training can resume. If the above factors are addressed re-injury is unlikely, but if tightness returns treatment should start then, before pain returns.

Hip Abductor (Gluteus Medius) strengthening:

1) lie on the unaffected side, with your bottom leg bent at the knee and the injured leg straight and lying on top of the bottom leg. Raise the injured leg, with the knee straight, to 30 degrees upwards, pause for one second, lower and repeat. Do not bring the thigh forward as the leg rises, and do not use your lower back muscles to raise the hip. Work up to repeating up to 20 times for two sets. When this is pain-free, the next exercise, done standing, can begin.

2) Standing, raise the uninjured leg with the knee bent. Without bending the knee of the injured leg, let your pelvis drop towards the uninjured side and then raise it by contracting the outer hip muscle (gluteus medius) on the standing, injured side. This is a small motion, but will fatigue a weak gluteus medius muscle by 10 to 15 repetitions. Again, work up to two sets of 20 repetitions.

This article is for informational purposes only and should not be used for personal advice or diagnosis without first consulting a health-care professional. If you have, or suspect you have an health-care problem, then you should immediately contact a qualified health-care professional for treatment.